The Purpose of a System is What It Does

Stafford Beer, a key figure in cybernetic management theory, gave us the helpful acronym POSIWID: “the purpose of a system is what it does.” Beer claimed that the intent of a system, or that of its creators and maintainers, is of little use to us if we want to understand the purpose of that system. Instead of analysing its design and its aims, we must instead observe its results. What the system produces, what outputs it generates from its inputs, is all that matters. After all, Beer suggests, there is “no point in claiming that the purpose of a system is to do what it constantly fails to do.”

POSIWID has been on my mind ever since I woke up to the aftermath of the TV debate between Biden and Trump last week. I like to think that I've been around the block a few times and that I am not so easily shocked by the events of mainstream politics these days, but I admit to being a little unsettled by the clips and quotes I saw when I looked at my phone that morning. Having long ago set my expectations around such spectacles to zero, I nonetheless felt like a new and even more dank chamber had been opened in the already vast and grimy dungeon of rhetoric that makes up contemporary political debate. Maybe it was just naive of me to think that, even in this environment, someone would intervene before it came to two geriatric men – both having been president already, one of them clearly senile – insulting each other on live TV. No, you suck, you’re the loser!

Once the light comedy of seeing these guys weaponise their golf handicaps had worn off, the surreal quality of the affair really began to sink in. Biden’s rambling on the topic of abortion was perhaps the clearest evidence of how inarticulate and pointless the entire evening was:

Look, there are so many young women who have been, including a young woman who just was murdered, and he went to the funeral. And the idea that she was murdered by an immigrant coming in, to talk about that. But here’s the deal. There’s a lot of young women are being raped by their in-laws, by their, by their spouses. Brothers and sisters, by—it’s just ridiculous.

I don't think it necessary to belabour this point: literally nothing of substance was said, by anyone, during the debate.

The conversation since then has centred on whether or not Biden should be asked to pull out of the race, and if so, who should replace him. This is the kind of thing that political correspondents live for—pure speculation, untethered from consequence, on what may or may not happen; whatever allows them to sound smart and well-connected today, even if proven entirely wrong tomorrow. Of course, I expect nothing more from that class of commentator. I certainly don't expect any structural analysis of how we reached this juncture. I don't expect reflection on the system they are all engaged in and dependent on, the purpose of which is evidently to produce this kind of spectacle. I have witnessed many versions of this spectacle over the last two decades, few as bleak as this one, but none at all that I would consider a positive experience. That the system continually fails to produce what it was ostensibly designed to produce - inspirational democratic leaders, moments of clarifying unity, articulations of dissent and difference - does not, it seems, lead any of these people to question the system itself.

Obviously the system does produce two incoherent and dishonest men shouting at each other. (It does not produce this only in the United States.) These are the representatives of the system, the embodiments of it. Fine, whatever, that’s obvious and people are always pointing it out. It is more significant that the system systematically fails to produce any alternative to this. Recognising this fact, we might begin to invert, or at least extend, Beer’s thought: what the system does not produce can be just as telling as what it does. Perhaps its purpose is to produce one thing at the expense of another; perhaps it produces what it does in order to obstruct the production of something else. In this sense, the purpose of the system is exactly what it consistently fails to do.1

My own political experience, over the last ten years in particular, has been one of repeat disappointment. It has also been a journey of trying to understand why the system is incapable of producing and sustaining any kind of alternative to a status quo that only a small minority of people actually respect or believe in. The Biden-Trump debate was just the latest evidence of a malaise much more general. The face-off between Starmer and Sunak in the UK the week before was no less distressingly inane. (James Butler has written with his usual perspicacity on that non-event for the LRB blog.)

Here in Ireland the recent local and European elections were considered victories for the two ruling parties of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, despite it being historically their worst ever local election performance, because it was expected that the results for those parties would be much worse than they turned out to be. Instead of establishment collapse, the narrative became how an increase in support for far-right/anti-immigration candidates went hand-in-hand with a predicted surge for Sinn Féin failing to materialise. I’m not suggesting Sinn Féin had a good election, they didn’t, but the rapid formation of consensus in the hours after the polls closed was still striking to watch. This election cycle’s shift in tone was drastic and pervasive: the kind of inflammatory racist rhetoric that in the recent past would have been latent (if not entirely marginal) was now front-and-centre, unavoidably mainstream.2 In the end, we were told afterwards, that was concerning, but not disastrous—the far right did not storm the polls this time, the centre managed to hold. The system continues to function as intended.

This ever-more-desperate appeal to stability did not work well during the Covid pandemic – when any kind of dissent or criticism was decried as conspiratorial, counter-productive, or mad – and it is not working well now. (As I write, the first round of exit polls from the snap election in France have just been published—more of the same may not be an option there after July 7th.) Over and over again, we hear the same things: there are issues but we need time to deal with them; we have a plan and we need to stick to it. A tweak here and a tweak there. We are working on that. And so on. Variants on a theme: we are the ones who know how this works, trust us—the alternative is much worse.

In times of crisis – and if the last fifteen years have been anything, they have been a time of constant crisis – this kind of messaging is rarely enough in itself. Trust in the institutions is so eroded, the discourse so polluted and unhinged, that more aggressive tactics are required to convince people of the need for ‘stability’. Suddenly everyone wearing a suit on television is talking about the need to be tough on immigration, tough on crime, tough on benefit scroungers, tough on any scapegoat that can be found. Worst of all are those who, coming from The Left, don’t row in behind the efforts of the ruling parties—don’t they know they’re opening the door for the far-right? Unity is vital. A vote for a third candidate is a vote for Trump—it’s her turn. Reaches are made: hundreds of thousands of mostly young people joining the UK Labour party is a bad thing; the image of Jeremy Corbyn appears on the BBC, mocked up in red hue, in front of the Kremlin, in a Russian hat. It goes on and on like this, the Overton window shifting until even the most ‘reasonable’ and popular policies (policies often unremarkably in place in many other countries) must be rejected out of hand as the ravings of madmen, cranks, and extremists.3

Everything must stay as it is, no alternative is possible.

All this to say, the point of contemporary democracy not to produce a political course of action that will benefit ordinary people; the point is to protect, at all costs, the operating logic of the system as it is. The important thing is to ensure that people who have spent their lives being the ‘pragmatic’, ‘reasonable’ types – always so in touch with reality, always lecturing others on the hard realities of grown-up politics – retain the power they have held over the institutions of government, business, and media for decades. It doesn’t matter if their predictions are wrong, it doesn’t matter if their policies are unpopular, it doesn’t matter if one party or the other is in power—things will stay the same. This is the system doing what it was designed to do.

The tragic thing, which cannot be openly acknowledged, is that even those who are most invested in things as they are seem to have little or no faith in the system’s ability to achieve its stated aims. Knowing that ‘the markets’ actually dictate their ability to act, the politician’s role, as far as they see it, is crisis management. Moving from scandal to setback to calamity, ‘centrist’ Anglophone governments respond but they do not lead. There is no vision at all for what democratic government can achieve beyond minor tweaks in taxation or regulation—this, perhaps more than anything, produces the cynicism and apathy so palpable around elections. The major issues in society – housing, healthcare, crime, pay, etc. – are complex and intractable (sotto voce: way beyond your ability to understand), and any serious attempt to solve them would only make you a pariah among the politically enlightened. It would also make you unelectable in the eyes of the media who, James Butler writes, “seem to have decided that honesty about this problem amounts to political suicide, and so we are left with politicians sedulously ignoring the chasm in our foundations and tap-dancing over the abyss instead.”

That abyss was presented to the public in an unusually frank manner by the Biden-Trump debate. The elections taking place across Europe this week, and in the coming months, will offer another opportunity to peek into the void.

What is the system? I mean the complex and multi-determined mass of people and concepts involved in the production of political discourse: politicians, lobbyists, advisors, union officials, journalists and the media more broadly, etc. I am speaking quite generally because I actually don’t want to pin blame on any specific person or party or publication—I want to think systematically; to understand how narrative and power and ideology work within that discourse, without getting hung up on someone being right and someone else being wrong.

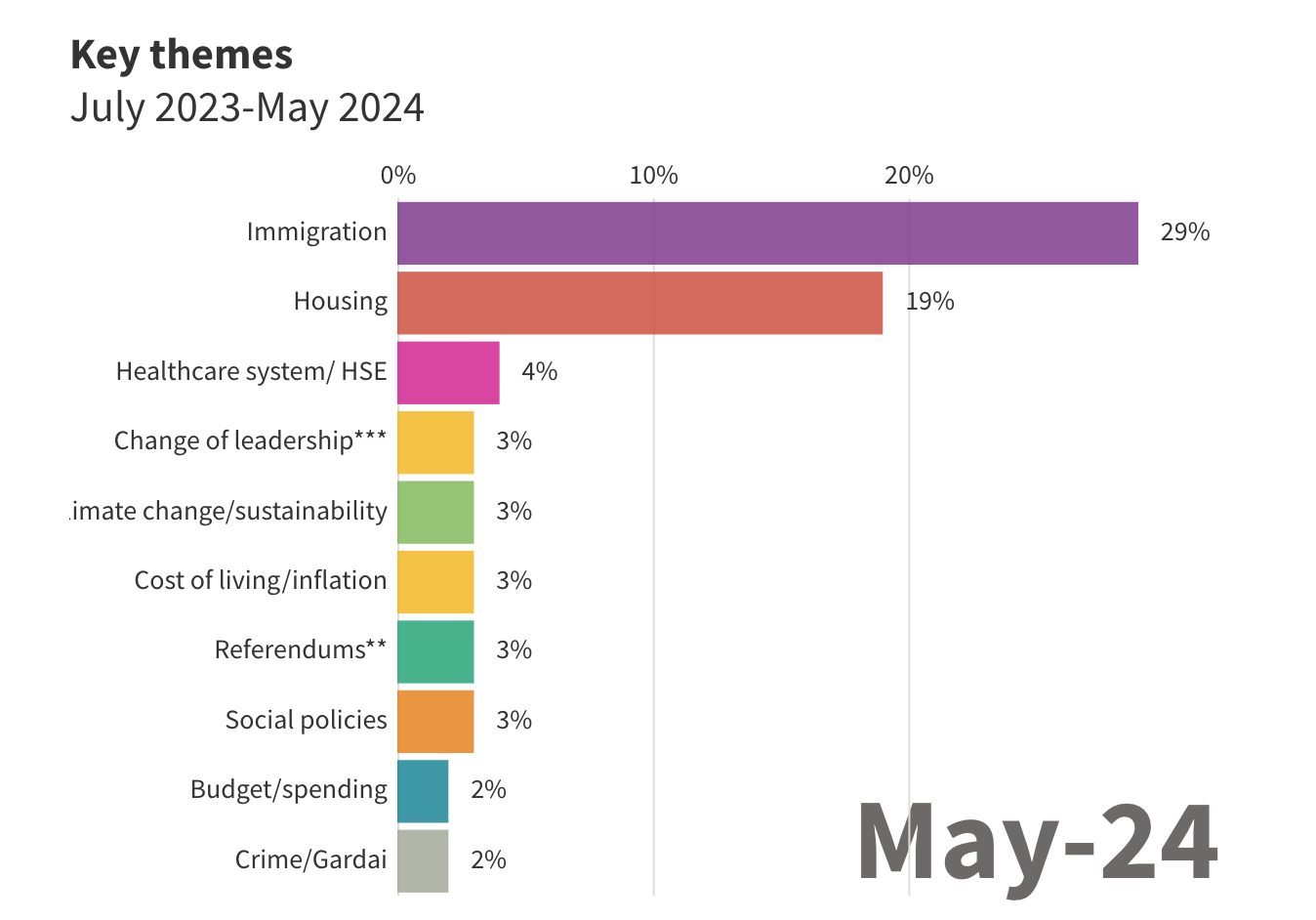

I watched with horror the animated Irish Times bar-charts, showing the changing results of opinion polls on what was the most important topic for voters; immigration coming from nowhere to top the poll in the weeks before the election.

I watched and thought, this must be intentional. It is clear that immigration is a sticky subject for a populist nationalist party like Sinn Féin, whose enlarged support over the last five years has been a product of bringing some ideologically distinct groups together under one banner. I have felt for some time that the ruling parties have allowed the issue of immigration to fester for two reasons: 1) their own base is significantly anti-immigrant so they don’t want to come out strongly on a divisive subject, and 2) they know that on this issue in particular Sinn Féin are caught between the two stools, unable to please either the left-leaning, college-educated urban votes who have flocked to them, largely for being strong on housing issues, or the older, working class, nationalist camp that still makes up a large part of their base. The party’s befuddled response to this ‘conversation’ in the run up to the election was noticeable—by trying to keep everyone happy, they managed to alienate both sides.

The motivated nature of this criticism is, curiously, perhaps clearest when it is directed at people, like Keir Starmer, who haven’t a radical bone in their body. Witness the front-page headlines in the UK this weekend claiming Starmer will ‘wreck the country in 100 days’, should he be elected.